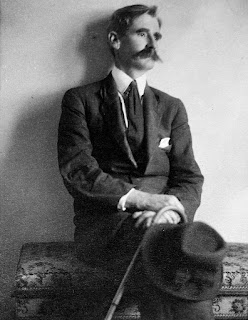

Henry Lawson

My sense of looking into, and learning about people from the past, is increasing as I mature. Perhaps these growing feelings have their genesis in the thoughts that my life, all our lives, are at best temporary moments in what I believe, is a much broader picture.

I have had occasion recently to look more closely into the lives of some literary people in particular who were poets / writers and citizens of the land of Australia, who have left such a legacy and beautiful presence in this land, for those with eyes to see, and hearts to feel.

I am going to start this short tribute series of historical Australian poets focusing on a man that was embraced, and in some measure shunned. He was thought of as an embarrassment by some of his peers. He was a simple, yet complex man. He was a man who travelled, a man who needed a lot of help, a man who was sensitive and a man who loved, and was loved. He was a man who was troubled, and a man who was jailed, and sadly a man who battled shyness, deafness, depression and alcoholism. He in fact relied on, and in very deed survived on, the generosity of some kindly people who loved and admired him. He could be any man in modern day Australia.

I am writing of Henry Lawson.

Before I tell the basic story of Henry Lawson, I note with understanding and sadness that there are almost no structures homes or buildings left from Henry's time that remain to this day. HOWEVER, after much research and walking I was able to locate a photo captured in 1905 in North Sydney that is held by the Royal Australian Historical Society that has remained largely the same some 119 years after that image was taken, and it was honestly surreal, and wonderful to see where Henry sat and walked, and I could not help myself but merge the present with the past of that picture taken so long ago.

I think it both fair, and sad to say, that the rising generation is seemingly not being exposed or introduced to these historical figures, anywhere near as much as I believe they should be, and would love to be wrong. People have said when I have enquired, “oh Henry Lawson?, don’t know him” And that is it.

I also realise that in my small social media posts, that few if any will read long posts, and I cannot adequately do justice to the lives of the people I will be highlighting with what little or much I am able to string together. I will do so however scant my writings may be, simply because of the respect and admiration I have for these people, and the gratitude I feel for what we have that remains of their moments here.

Henry Hertzberg Lawson was born in a tent near Grenfell, N.S.W., on June 17, 1867. His father was Peter Hertzberg Larsen, a Norwegian sailor, who was well educated. Peter married Louisa Albury, who was born at Guntawang, near Mudgee in 1848 and was eighteen when she married. Mrs. Lawson was a remarkable woman, with many graces of character, destined to take a conspicuous and honourable part in public affairs in the years to come. She died in August, 1920, at the age of 72.

Lawson was reared in circumstances that today would be considered those of poverty.

The man who would become one of Australia’s most famous and loved writers in fact only received three years of formal schooling. There wasn’t even a school when the Lawsons moved to Eurunderee – it was Louisa Lawson who pushed for one to be built. And even though young Henry only attended the Eurunderee Provisional School for a few years, he had a soft spot for the ‘old bark school’, writing about it, visiting it years later and even entering an impromptu poem in the visitors’ book.

Louisa, an impressive figure throughout Lawson’s life, also ran the local post office in her husband’s name and no doubt inspired Lawson’s later stories about the strength of women living in the bush.

A shy boy, Henry was bullied at school and also suffered an ear infection, which, by the time he reached 14, had cost him most of his hearing. If there could be any upside, it’s that the condition contributed to his creativity – Lawson later claimed that his deafness' was to cloud my whole life, to drive me into myself, and to be, in great measure, responsible for my writing.'

Henry Lawson worked in various shops and did occasional house painting, and was often unemployed. “I know what it was then,” he writes, “to turn out shivering at 4 o’clock in the morning and be one of a hungry group striking matches and running fingers down the wanted columns of a freshly printed Herald — to drift all day through the streets in shabby old clothes, and feel fugitive and criminal.”

One day, seized by a sudden impulse, he began to write. He posted what he had written to Mr. John Archibald, and then waited in an agony of suspense for an answer. Unable to bear the suspense he mustered courage after a few days to make personal inquiry. Archibald often told the story of their first meeting, which seems to have amazed equally the two parties to the interview. A day or two later he saw his first verse in print — the fiery “Song of the Republic.” That was in October, 1887.

The publication of this verse was the turning point in Lawson’s life. The painting days had gone now. Lawson had entered the ranks of accepted writers. The rest of his life was devoted, with occasional interruptions, to the work that made his name so well known all over the Commonwealth. There were visits to London and New Zealand. A widow and a son and daughter survive him.

One shilling: that was the price of Henry Lawson’s first published book, Short Stories in Prose & Verse.

Louisa Lawson (mum) published it in 1894, having found commercial success with her second project, the women’s paper, Dawn, and used the paper’s press to print her son’s book. An accident on the way to the binders saw many pages blow out of the printer’s cart into York Street Sydney, and only 300 copies were saved. One of the 70 known surviving books is held in the Mitchell Library in Sydney City today. Henry Lawson’s inscription to David Scott Mitchell (a noted bibliophile and collector of publishing curiosities) reads:

Dear Mr Mitchell,

This is my first book. Only a few copies were published, fortunately [as] I withdrew the book from publication. The book should be interesting as a curiosity in printing.

H. Lawson

The poorly edited volume of 96 pages, printed hurriedly for the Christmas market, brought in little money despite good reviews. But the literary legend of Henry Lawson was gaining momentum.

Among the friends and colleagues who were there for Henry Lawson in bad times as well as good, he was always grateful to his publishers J.F. Archibald and George Robertson. J. F. Archibald, editor of the Bulletin and founder of Australia’s famous portrait award the Archibald Prize, was a long-time supporter of writers and artists. It was Archibald who helped Lawson in his early days as a Bulletin author, guiding him through his kindness and sensitive editing to shape his unique, laconic writing style. Lawson would later dedicate In the Days When the World Was Wide to Archibald. The editor died in 1919 and is buried at Sydney’s Waverley Cemetery, the same place Lawson lies.

Publisher George Robertson was also a great support to Lawson, both personally and professionally. Lawson wrote the poem ‘The Auld Shop and the New’ which, Lawson claims on the title page, was ‘Written specially for “The Chief”, George Robertson, of Angus and Robertson, as some slight acknowledgement of and small return for his splendid generosity during years of trouble.’

Henry Lawson’s sensitive and precise observations, with his inimitable writing style, brought a nation one of its first voices. He introduced concepts of Australian identity, of city and country life, battlers and survivors, larrikins and heroines and unforgettable characters in both worlds are in large part due to his creations. Lawson will always be remembered for the sentiment of his poems and the writing in his short stories, and while his own tragic tale of disillusioned life had a detrimental effect on his work and wellbeing, it has become a part of the literary legend we remember now.

To the end of his life Lawson was exceptionally shy among strangers and always oddly sensitive. In those earlier unfruitful days of poverty and repression — isolated and driven in upon himself by deafness, and out of tune with his environment — his shyness was almost a disease. He became embittered in mind, aloof, and sombre in bearing, retreating in habit.

The Sydney Morning Herald wrote this tribute on the day Henry died on 4 September 1922

“The death took place on Saturday morning of Mr. Henry Hertzberg Lawson. He was 55 years of age. His contributions to Australian literature, alike in the domain of poetry and of prose, had won for him an enduring and notable place in its annals.

Mr. Lawson’s remains will today be accorded a State funeral - fitting tribute to one who, in the great commonwealth of letters, has left the indelible impress of his genius. For a long time Henry Lawson’s health had by no means been robust, although he was not confined to his home. Latterly he had lived at a cottage on Great North Road, Abbotsford, and during last week he visited the city, where he transacted some business. On Friday evening he had a seizure, and was assisted to bed, and was never quite conscious afterwards. On Saturday morning at about half past 10 o’clock the end came”.

The then serving Prime Minister (Mr. Hughes), referring yesterday to Henry Lawson’s death, said: “Henry Lawson’s memory is enshrined in our hearts. It was my privilege to know him, and to range myself with that great host of Australians who admired and loved him. His death has left a gap that will not soon be filled. He knew intimately the real Australia, and was its greatest minstrel. He sang of its wide spaces, its dense bush, its droughts, its floods. He loved Australia, and his verse sets out its charm, its vicissitudes. None was his master. He was the poet of Australia, the minstrel of the people.“

'Faces in the Street’ - then and now

1888

Another rainy night on Petersham platform …

This famous Lawson poem has strong connections to Petersham Railway Station in Sydney’s inner-west. A plaque on the platform commemorates the fact that it was while waiting for a train one rainy night in 1888 Lawson, then a young man of 21, struck the poem’s keynote stanza:

They lie, the men who tell us in a loud decisive tone

That want is here a stranger, and that misery’s unknown

For where the nearest suburb and the city proper meet

My window sill is level with the faces in the street.

It was built of bark and poles, and the floor was full of holes

Where each leak in rainy weather made a pool;

And the walls were mostly cracks lined with calico and sacks –

There was little need for windows in the school.

– ‘The Old Bark School’, 1897

Run of rocky shelves at sunrise, with their base on ocean’s bed;

Homes of Coogee, homes of Bondi, and the lighthouse on South Head.

For in loneliness and hardship - and with just a touch of pride -

Has my heart been taught to whisper, ‘You belong to Sydney-Side.’

– ‘Sydney-Side’, 1898

No church-bell rings them from the Track,

No pulpit lights their blindness –

‘Tis hardship, drought and homelessness

That teach those Bushmen kindness

(‘The Shearer’, 1901)

‘Oh, I dreamt I shore in a shearin’ shed, and it was a dream of joy,

For every one of the rouseabouts was a girl dressed up as a boy’

(‘The Shearer’s Dream, 1902)

I loved to stroll about the town

With chums at night, and talk of things,

And, though I chanced to wear the crown,

My friends, by intellect, were kings.

– ‘When I Was King’, 1904

With his hideous dress and his heavy boots, he drags to Eternity -

And the Warder says, in a softened tone: ‘Keep step, One Hundred and Three.’

– ‘One Hundred and Three’, 1908

By track and camp and bushman’s hut - by streets where courage fails -

I’ve sung for all Australia, but my heart’s in New South Wales.

(‘Bonnie New South Wales’, 1910)

The Song of Australia

The centuries found me to nations unknown –

My people have crowned me and made me a throne;

My royal regalia is love, truth, and light –

A girl called Australia – I've come to my right.

Though no fields of conquest grew red at my birth,

My dead were the noblest and bravest on earth;

Their strong sons are worthy to stand with the best –

My brave Overlanders ride west of the west.

My cities are seeking the clean and the right;

My Statesmen are speaking in London to-night;

The voice of my Bushmen is heard oversea;

My army and navy are coming to me.

By all my grim headlands my flag is unfurled,

My artists and singers are charming the world;

The White world shall know its young outpost with pride;

The fame of my poets goes ever more wide.

By old tow'r and steeple of nation grown grey

The name of my people is spreading to-day;

Through all the old nations my learners go forth;

My youthful inventors are startling the north.

In spite of all Asia, and safe from her yet,

Through wide Australasia my standards I'll set;

A grand world and bright world to rise in an hour –

The Wings of the White world, the Balance of Power.

Through storm, or serenely – whate'er I go through –

God grant I be queenly! God grant I be true!

To suffer in silence, and strike at a sign,

Till all the fair islands of these seas are mine.

Comments