Lewis Morley

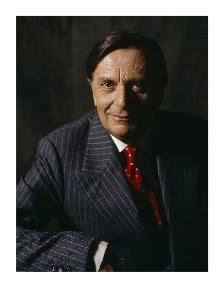

At the exhibition with Nafisa Naomi on Tuesday night I had the chance to meet and photograph the world famous and accomplished photographer Lewis Morley. I will include some biographical data about him and some of his famous pictures and do a sum up at the end.

Photographer Lewis Morley deftly captured the spirit of '60s Britain, writes Robert McFarlane of The Sydney Morning Herald.

Myself and Eye, on show at the new lakeside exhibition space of Canberra's National Portrait Gallery, surveys Lewis Morley's long and serendipitous life as a photographer.

Morley appears to have enjoyed at least three lives while successfully pursuing two discrete careers. Born in 1925 to an English father and a Chinese mother in Hong Kong, he grew up as a member of the most privileged Eurasian class in the then-British colony, until his adolescence was rudely interrupted with internment by the Japanese army in 1941.

"People say life in the camps was terrible," Morley told me recently at the National Portrait Gallery. "But I was lucky. I worked in the kitchens at Stanley Internment Camp and got extra food. I also had a girlfriend in the camp. And you could trade anything for a couple of cigarettes."

When Morley was a teenager, his photography was only a hobby practised on a plastic Bakelite Brownie camera. What really interested him during his captivity were drawing and painting with watercolours. "I used to swap cigarettes for paints and paper," he said. "My drawings weren't very good but it was a start. I still have some of those pictures."

After the war his family were repatriated to London, where he enlisted in the Royal Air Force. The dandy in him justified his choice of becoming an airman by declaring, "I look better in grey."

When he left the air force, he studied commercial design, enrolling at Twickenham Art School between 1949 and 1952. Five years later, he was accomplished enough with his Exakta and Leica cameras for Norman Hall, the influential editor of Photography magazine, to publish six pages of his pictures, praising him as the latest young British discovery.

But it would be the next decade that established him.

He became friendly with the comedian Peter Cook, who offered him studio space above his satirical nightclub, The Establishment. The comedian would become both a regular subject for Morley and his friend and landlord.

Quite by chance, Morley found himself near the centre of social and artistic change in London.

His early style reveals him to be more than competent as an observer of people - witness his 1957 picture of a rainswept bride being led into a London pub, or an elegant 1958 observation of a lone newspaper reader in the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris.

But he would soon reveal a distinctive talent for studio portraiture. His 1963 nude of Christine Keeler, softly lit as she straddled an Arne Jacobsen chair, quickly became a symbol of the fragile politics of the '60s.

But looking past this image's notoriety (it has been published hundreds of times throughout the world, often without Morley's permission), it is still remarkable for the calculated, intimate response Morley coaxed from the political courtesan who had just ruined the career of a British minister, John Profumo. "It was the very last shot on the roll," Morley told Myself and Eye's curator, Magda Keaney. "I was walking away and turned back. She was in a perfect position and I just snapped it."

But Morley later admitted to me: "I never found her sexy, though. She reminded me too much of Vera Lynn!"

He produced fine portraits of other key '60s figures - an earnest, peach-faced Susannah York caught in close-up in 1965 and an apparently mundane portrait from the same year of Andre Previn.

He showed the slightly chubby young musician sitting at a hotel room table scattered with breakfast debris.

What lifts this image for me is the precision with which Morley captured Previn's introspection.

A commission in 1961 to take publicity portraits for the Beyond The Fringe satirical revue led to another memorable picture - of the comedian and musician Dudley Moore. "I was photographing the four boys [Moore, Peter Cook, Alan Bennett and Jonathan Miller] and I looked around and Dudley was lagging miles behind," recalled Morley. "I shouted, 'For Christ's sake, Dudley, come on!' and suddenly he hunched over and posed like the Hunchback of Hyde Park and I snapped it."

Magda Keaney explores these natural extremes in Morley's subject matter, such as in a shot of two naked young women quietly smoking marijuana at a 1965 London party.

Many of his London photographs are similarly artless observations with little sense of having been directed. However, Barry Humphries received special treatment in 1963. For his friend, Morley created a slightly surreal confection in which the facade of The Establishment nightclub was superimposed over the wanly gesturing, lank-haired satirist. The resulting image now seems excessively mannered, but undeniably of its time.

Morley is rightly acclaimed for his documentation of '60s Britain, but a second, longer career began when he and his family emigrated to Australia in 1971.

Keaney ignores the prodigious interior and food photography produced by Morley for BELLE and Woman's Day, concentrating instead on the portraits he made for these and other Australian women's magazines - including the influential POL, itself the subject of a parallel show at the National Portrait Gallery's Old Parliament House space.

For his Australian portraiture, Morley embraced and mastered colour photography, producing a number of valuable observations of significant Australians. His 1975 portrait of Junie Morosi (far sexier than Christine Keeler, Morley confided) conveyed her sensuality and intelligence in equal measure.

His best pictures flow from a certain playfulness with the camera, reinforced by his ability to establish rapport with disparate subjects. His work attempts to capture joyfully the nature of experience, a philosophy also espoused by the late French photographer Jacques Henri Lartigue, whom he now rates above his first inspiration - Henri Cartier-Bresson.

As we left the gallery, I asked Morley what he thought about his life's work, now that it was finally on display. He smiled, then replied that if he walked into the show and didn't know who took the pictures, he would have said "Not bad!"

These 4 pictures are all of Barry Humhpries with his 3 alter egos taken by Lewis Morley. If you can get one they sell for around $15,000.

As I indicated at the start, I got to meet and chat with this wonderful man. I said to him how I admired his work, what he had done and who he has come to know through his work. He said, "You are passionate about this aren't you?, to which I responded "yes, it honestly helps get me up in the morning!" He said, "you know, I feel guilty when I meet people like you, and others I know who have talent and are passionate about what they do, and have not achieved what I have". Curious, I asked for clarification. He added "I feel guilty because, I am not passionate about photography. I sort of fell into it because I wanted to be a painter. It is not something I planned on". Then he said to me almost to convey a secret, "would you like to see what I use these days" after glancing at my camera and large lens. I said "sure", thinking he would allow me to visit his studio or home and then he slyly parted his jacket and produced a small Kodak digital camera and said, "this is what I use these days." I asked if I could take a picture of him with it, indicating I would send it to Kodak, he said "sure", and we had a face off of cameras taking pictures of each other. I sent it to Kodak, and they loved the story and will publish it with my images in their Kodak Expressway publication, in the next issue.

A lady in charge of the Art trust of Sydney approached me saying how much she regretted not having a camera to take a picture of Lewis and I taking a picture of each other. It was a moment in time that she froze in her imagination. I shared the mental image of the moment. It was a great thrill for me. Simple, but very special for me. Lewis smiled and said; "all the best to you, keep working at it!".....and I shall. Thank you Lewis.

A post script note here is, that an observation made by another media presenter in Sydney, said something that made me agree, that Lewis is devoid of an ego at all. He is a warm and genuine man who made me and everyone else that drew near to meet him, feel warm and important. A rare experience and one that I shall not forget in a hurry.

I have included a picture here as well of me with the wonderful Maria Venuti, who was also at the gallery. What a wonderful lady she is.

Comments